Earlier I shared a video from Colin Low about the history of the Tarot. He does a marvelous job of tracking and explaining whence these cards came, and when they came to be used for things other than playing a card game – things like meditation and divination and obtaining guidance and insight.

It’s an excellent video and I’d highly recommend it to anyone with an interest in the cards or in the art of Tarot reading. For me though, it left open a fascinating and really important question. How did we get this specific set of 78 cards that we know and use today? How did the cards congeal into the form of the Tarot de Marseilles?

Here’s what we know.

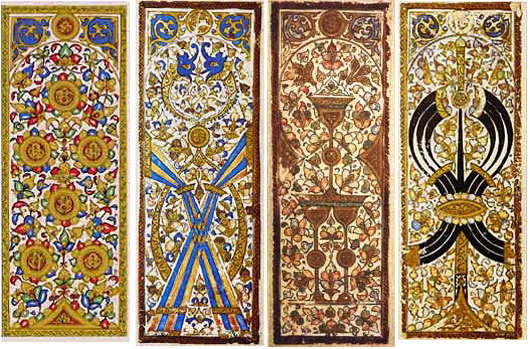

We know that the cards of the four suits came to Europe from the Islamic world as the Mamluk playing cards. These cards had four suits of an Ace, three Court Cards and nine pip cards each. We also know that “permanent” trump cards were added at some point to make the trick-taking game more interesting and unpredictable. The trumps depicted characters or scenes which would have been familiar to most Europeans in the 15th Century. From what we can tell, though, these cards varied widely for a time, both in terms of how many there were and in what they portrayed.

So how did we get the deck in this final form that we have now? The deck of 22 Majors, and four suits (of Ace through Ten plus King, Queen, Knight and Page) has been the standard since the Marseilles deck appeared. But why?

Why does it matter?

The reason that this question is of interest is because this deck is so perfect in its correspondences to all sorts of ancient wisdom traditions. We have 22 majors, and they correspond perfectly to the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet and the 22 paths on the Tree of Life. They correspond to the three elements and seven planets of the Ancients and the twelve Astrological Signs.

Then we have the four suits which correspond to the elements of Fire, Water, Air and Earth (and the four dimensions of Spirit, Emotion, Mind and Body). We have the nine pip cards in each suit, and altogether those correspond perfectly to the 36 decans of the Zodiac wheel.

These correspondences go on and on, and they work together in such a way as to create a complex and coherent system of meaning, beyond that which we might expect from any coincidental arrangement or assignment. The Tarot works, and makes sense, in such a way that it is tempting to believe that some genius, or conspiracy of geniuses, must have created it with great care and intention. It gives the appearance that a comprehensive system of special knowledge came first, and that it was then encoded into the card deck.

In fact, this idea is so tempting that despite all of the historical evidence to the contrary, it is what some people still believe. An ancient sect (probably an Egyptian Mystery School) took the secrets of the Universe, and hid them in these 78 images, and then passed them along through generation after generation of initiates, until they were finally brought to Europe by their heirs, the Romani.

Despite the attractiveness (and the romance), this story just doesn’t stand up to reasonable scrutiny. So we are left with a few possibilities.

Maybe the Tarot deck came to embody such a marvelous and powerful system of meaning purely by happy accident. Or perhaps there were hidden actors involved, crafting the deck at key moments in its history to bring us the Tarot that we know today. Perhaps it was revealed to the printers in Marseilles by Divine Revelation.

Or perhaps the truth is even stranger and more amazing.

The Conspiracy Revealed

What if, deep within each of us, there are predispositions toward certain shapes, and numbers and images? Twelve notes in a musical octave. Seven notes in a major scale. Twelve signs of the Zodiac. Seven planets of the ancient world. Three ancient elements. Three dimensions in space. The Holy Trinity. Twelve Apostles. Seven Churches, Seven Lampstands, Seven Seals in John’s Book of the Apocalypse. Twelve Tribes of Israel. Threes. Sevens. Twelves. Rinse and repeat.

Three plus seven plus twelve equals twenty-two. Twenty-two paths on the Tree of Life. Twenty-two Hebrew letters. Twenty-two regular polygons which can be inscribed in a circle. Twenty-two cards in the Major Arcana.

We have predispositions, and they want to find expression. This is what culture does. There’s all of this stuff, and it all competes for our attention. Some of it gets attention for a little while, and then it combines with something else. And it all gets shaken and strained and heated and sifted and pulled apart, and this process goes on and on until we eventually get *some* things that reflect a culture’s habits of attention in a more essential way – things that define a human culture.

We are conditioned by the nature of what we experience as material reality, without the need to be taught, toward a preference for these primordial shapes and numbers and ideas – these archetypes. Our habits of attention work without the need for discussion or planning or overt agreement or conscious intent. These preferences are imprinted deep in each of us, and eventually we imprint them on the things that we create, whether intentional or not. Themes recur across cultures and across the ages. Truth manifests.

So it was a conspiracy of geniuses that gave us the Tarot deck as we know it. We are that conspiracy.

This could well be why the Tarot has such strong correspondences with systems of sacred knowledge from across diverse cultures and times, and also why it remains such a singularly powerful and compelling tool, even in our day.